I have been working on the Elephants and Bees, Sri Lanka project for almost 3 years now and am pleased to report that our pilot study is going well.

Our first year, back in 2014, was a very busy year of planning – visiting villages, learning from farmers about the many challenges they face living alongside elephants including the damage to crops and property inflicted during crop-raids, and determining which village and farms were most suitable for our pilot study. This lengthy period enabled me to form a strong local team, headed by my field assistant and translator Supun Herath, to begin to know the local farmers and let them get to know us, and to begin to learn about the many complicated and conflicting interactions between humans and elephants.

Our research site is located in Dewagiriya Village, Matale District, Central Sri Lanka. Located near to Wasgamuwa National Park and the Mahaweli River, Dewagiriya Village experiences almost year-round crop-raiding. Farmers rely on their crops – primarily rice – to feed their families and to sell at markets to generate income. From preparing fields, to planting, to harvesting, to storing harvests in their homes, farmers are always at risk from crop-raids and need to vigilantly protect their farms and houses.

To paint a picture of their ongoing challenges, since late 2014, farmers have reported more than 300 elephant events in Dewagiriya village with damage occurring approximately 75% of the time. Some damage is relatively small – a few banana trees perhaps – but it is not uncommon for substantial sections of paddy fields to be damaged in a single crop-raid, or for sections of houses to be knocked down, sometimes while the family is sleeping inside.

Farmers from Dewagiriya Village receive only minimal outside assistance to protect their crops – a few firecrackers to scare the elephants away – and interest and enthusiasm for setting up a beehive fence trial was high. We selected 10 of the worst affected households, scattered about the village, and working with the local community, we built 10 beehive fences to protect homes and home gardens.

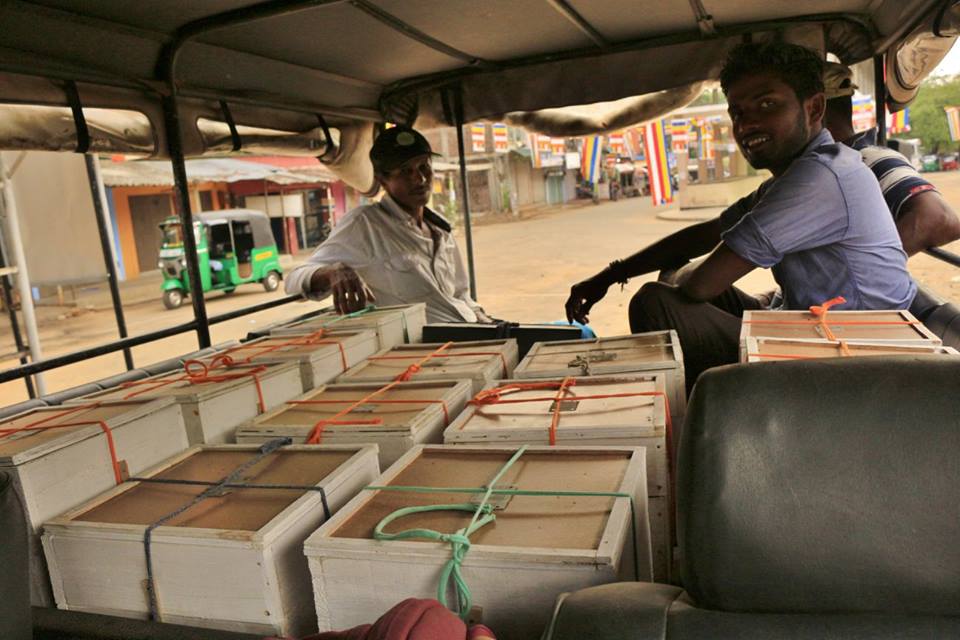

Bee colony delivery.

For the last year and a half, we have been monitoring elephant activity around the fences – collecting data on elephant sightings both inside and outside fence boundaries from farmers, and using camera traps to try and identify the sex and group size of crop-raiders. We also work continuously with farmers to keep fences well-maintained and to increase their beekeeping skills.

While it is still too early to determine the success rate of beehive fence as an elephant deterrent at our field site, we have seen some promising signs. Elephants have broken through the fences on a few occasions, however with the exception of one raid, only near unoccupied hives. Farmers have also taken small amounts of honey from their hives and are slowly beginning to experience additional benefits of beekeeping.

Right now, our main focus is on improving beekeeping skills, so farmers are able to manage their own hives. We have two experienced beekeepers visiting our field site next month to spend two weeks workshopping and training with the farmers. Additionally, increasing hive occupations, so that the deterrent effect of the fences is higher and we can predict the deterrent effect with confidence, is another priority.

I will be at our field site in Sri Lanka for the next three months and look forward to posting updates as we learn more about the potential of beehive fencing as an Asian elephant deterrent along the way!